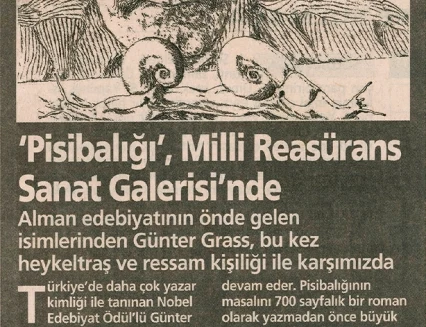

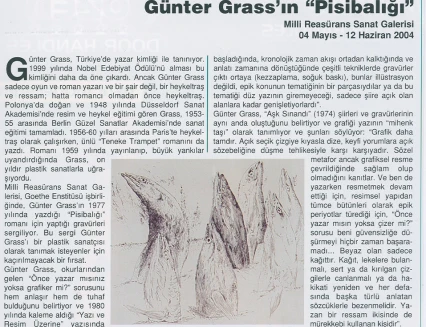

Günter Grass’s “Flounder” at the Milli Reasürans Art Gallery

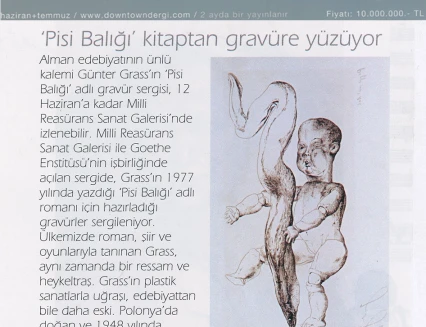

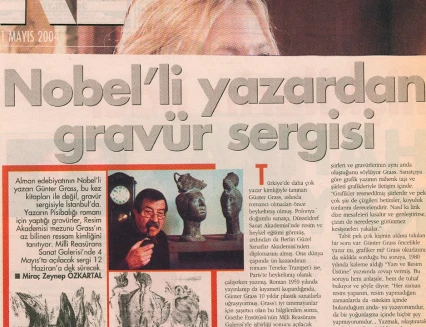

The engraving exhibition “Flounder” by Günter Grass, one of the leading figures in German literature, can be seen at the Milli Reasürans Art Gallery between May 4 and June 12, 2004.

A book has also been published for the exhibition organized in collaboration with the Goethe Institute in Istanbul.

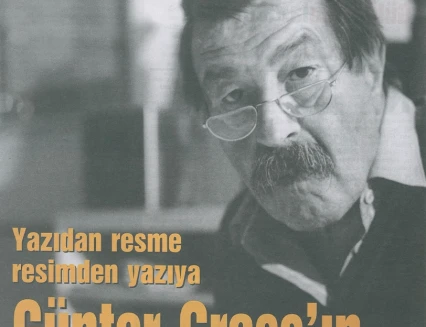

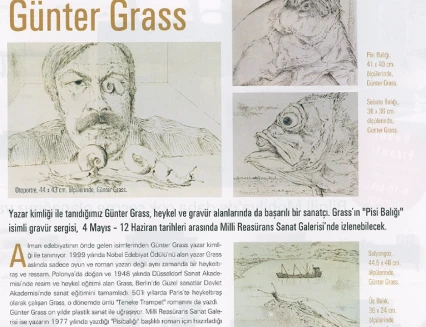

Günter Grass is known in Turkey as a writer. His Nobel Prize in Literature in 1999 brought this identity to the forefront. However, Günter Grass is not only a playwright and novelist and poet, but also a sculptor and painter; in fact, he was a sculptor before becoming a novelist. Born in Poland and studying painting and sculpture at the Düsseldorf Art Academy in 1948, Grass completed his art education at the Berlin State Academy of Fine Arts between 1953-55. While working as a sculptor in Paris between 1956-60, he also wrote the famous novel “Tin Drum”. When his novel was published in 1959 and caused a great stir, Grass had been working in plastic arts for ten years.

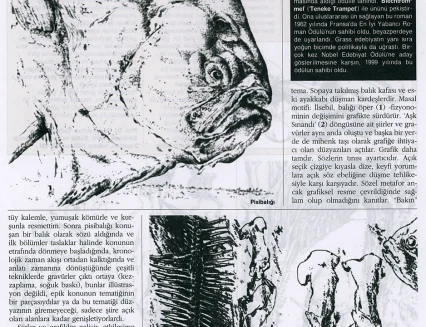

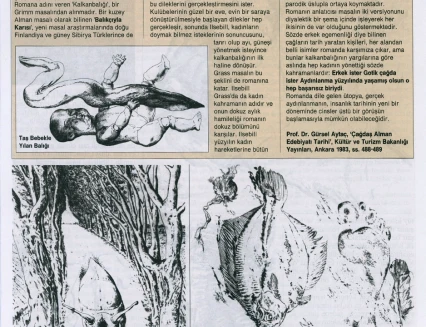

The Milli Reasürans Art Gallery, in collaboration with the Goethe Institute, is exhibiting the engravings Günter Grass made for his novel “Floatfish” written in 1977. This exhibition is an opportunity not to be missed for those who want to get to know Günter Grass as a plastic artist.

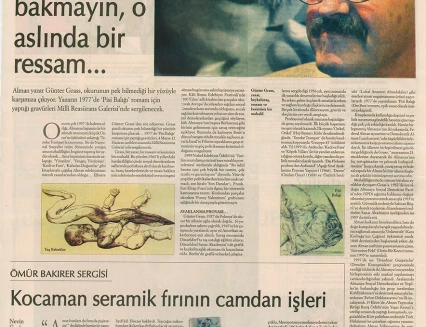

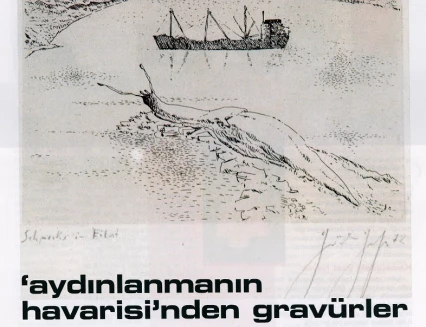

Günter Grass states that he finds the question of his readers, “Are you a writer or a graphic artist first?” both understandable and strange, and says the following in his article “On Writing and Painting” written in 1980: “I always paint, even when I am not painting; indeed, at the moment I am in, I am either writing or doing nothing in a state of concentration. Moreover, when I am painting, sentences that have started on another piece of paper continue to write themselves. Writing destroys time by compressing or dragging it along. Expression in a narrower area finds itself in painting. Before writing the tale of the flounder as a 700-page novel, I painted the large flat fish with a brush, a quill, soft charcoal and lead. Then, when the flounder took the floor as a talking fish and the first chapters began to revolve around the subject as drafts, when the chronological time flow disappeared and turned into narrative time, engravings in various techniques emerged (vitreous etching, cold printing), these were not illustrations, they were part of the thematics of the epic subject or they were they were expanding it to areas that prose could not enter, that were only open to poetry.”